In 2015, author Ken Liu stepped up to the podium at Sasquan, the 73rd World Science Fiction Convention, to accept the Hugo Award for Best Novel on behalf of Liu Cixin, author of The Three-Body Problem. It was a historic moment: Liu Cixin’s novel was the first translated novel to ever win the award, one of the highest honors in SF/F fandom.

Precipitating this moment is a long history of science fiction in China. The genre enjoys its own vibrant tradition of speculative works, developed over the past century. Liu Cixin’s award came at an interesting time for China: the Asian nation has become a major political power in the world, and as it grows, its authors and culture are reaching new, global audiences, introducing the western genre culture to new worlds of ideas and stories.

This post was originally published on the B&N Sci-Fi & Fantasy Blog in December 2015. Today is the Chinese New Year — the year of the Ox — and I’m using the occasion to republish it here with some heavy edits and updates from that original post.

Realizing modernity

Beginning in August of 1894, the Qing Dynasty of China and the Japanese Empire faced off against one another for control over the Korean peninsula in the first Sino-Japanese War. The tiny island nation of Japan was far more technologically advanced than its larger counterpart, and the conflict went badly for China, which eventually sued for peace months later.

The defeat was a major surprise, and it prompted the country’s leaders to begin rethinking how it would compete with its neighbors and global competitors throughout the world and how they could bring China into the future. One such thinker, Kang Youwei, “described China as ‘enfeebled’ and ‘soundly asleep atop a pile of kindling.'” Another intellectual, Liang Qichao, “believed that China’s sclerotic culture and general backwardness could only be remedied via a massive infusion of Western ideas and thoughts,” and advocated for China to emulate some of the practices which Japan had adopted.

The Guangxu Emperor of the Qing Dynasty was receptive to Youwei’s ideas and proposals, and instituted “100 Days of Reforms,” styling his programs after those of other major western leaders. These reforms were wide-ranging and covered every facet of Chinese life: the military, schools, governmental offices, and more. However, the program was largely a failure: only a single province instituted the changes, and Youwei and his associates fled to Japan.

In 1900, an anti-foreigner society known as The Boxers sparked another conflict, which escalated into a foreign invasion of Beijing and ensured western access into China. The Boxer Rebellion prompted a new progressive reformation in the country, which injected a wealth of western values into the country.

Chinese science fiction begins

As part of this movement, one Chinese author, Lu Xun, became aware of science fiction when he read a translation of Jules Verne’s novel De la Terre de a la Lune, (From the Earth to the Moon), serialized in a Chinese magazine called New Fiction. The magazine, founded by Liang Qichao, was instrumental in bringing western literature into the country, and featured other translations from Liang, like Captain at Fifteen and Twenty Thousand Leagues Under the Sea, which were followed by numerous others, which profoundly influenced Lu.

Lu was one of China’s leading literary intellectuals, and is considered one of the pioneers of modern Chinese literature. Born Zhou Zhangshou in 1881 in Shaoxing, Zhejiang, he resisted his family’s calling to public service in local government, and entered the Jiangnan Naval Academy in Nanking, before transferring to the School of Railways and Mines. Both schools emphasized a western approach to education and knowledge, and following his graduation in 1901, he entered Kobun College in Tokyo.

By this point, the Chinese government had begun to impliment a number of educational reforms, according to Albert M. Craig in The Heritage of Chinese Civilization:

“Women, for the first time, were admitted to newly formed schools. In place of Confucianism, the instructors taught science, mathematics, geography, and an anti-imperialist version of Chinese history that fanned the flames of nationalism … By 1906, there were eight thousand Chinese students in Japan, which had become a hotbed of Chinese reformist and revolutionary studies.”

In addition to Lu, other authors, like Liang, were beginning to produce their own science fiction stories at this time. Liang wrote Xin Zhongguo Weilai Ji (The Future of New China) in 1902, with the idea that scientific knowledge could be imparted to readers through literature.

Xia Jia, writing for Tor.com, noted that China was going through an incredible transition by this time:

“’Chinese Dream’ here refers to the revival of the Chinese nation in the modern era, a prerequisite for realizing which was reconstructing the Chinese people’s dream. In other words, the Chinese had to wake up from their old, 5000-year dream of being an ancient civilization and start to dream of becoming a democratic, independent, prosperous modern nation state. ”

As a student, Lu travelled throughout Japan, and eventually attended medical school in 1903. While doing so, he came across a Japanese translation of Verne’s novel, now titled Travelling on the Moon, translated by Inou Tsutomu. In the preface to From the Earth to the Moon, Lu wrote about why he felt so strongly about translating the stories into Chinese: he wanted to use the genre style as a means to improve the country:

“More often than not, ordinary people feel bored at the tedious statements of science… Only by resorting to fictional presentation and dressing scientific ideas up in literary clothing can works of science avoid their tediousness while retaining rational analyses and profound theories.”

It’s hard to understate the environment in which China found itself: many felt that the status of their country was in mortal danger of being overwhelmed by outsiders, and that society was unequipped to move into the future. Writers and intellectuals felt that it was a national duty to bring China in line with their Western counterparts.

His translation is a sort of adaptation, one that expands upon the original narrative, while drawing in additional references and influences from Chinese oral tradition.

Lu would later become known as the founding father of modern Chinese literature, and helped to unleash a new movement within Chinese literature, followed by other translators. According to Shaoyan Hu, writing in Amazing Stories, “translated science fiction works served as nourishment for the development of its Chinese counterpart. Chinese writers began to take their own initiatives to write science fictions.” Many of these stories were published in the country’s newspapers and began to reach broad audiences.

An example of one of these early science fiction stories was Tales of the Moon Colony, written by Huangjiang Diaosou. Serialized between 1904 and 1905, it followed a man who invents a hot air balloon, intending to fly to the moon. He never ended up completing the story, but as published it incorporated a number of technological advances of the time.

Science fiction had arrived, and as Nathanial Isaacson notes in Science Fiction Studies the genre was, “an anomaly of the emergence of science fiction in China that while the genre associated its origins with the translations of western imports, ‘science fiction’ (kexue xiaoshuo) began to appear regularly in China as a generic category associated with specific stories before it did so in the English-language press (circa 1904).”

Another story, 1910’s New China by Lu Shi’e, chronicled the life of a man who wakes up in a future Shanhgai in 1950. There, he discovers a “progressive, prosperous China, and is told that all this is due to the efforts of a certain Dr. Su Hanmin, who had studied abroad and invented two technologies: ‘the spiritual medicine’ and the ‘awakening technique’.” The inventions had allowed China to shake off its moral issues and, unburdened by their weight, advance rapidly in the international world.

Many of these stories followed a similar path and outlook on the world as their Western counterparts: their authors imagined a world changed by the introduction of new technologies that were rapidly overtaking the world. While the West had a considerable head start on the technological revolution, China was catching up, and artists had begun to recognize the implications. Where scientific romances in the West were examining technology’s influence on society – and in some cases, its downsides – their Chinese colleagues recognized that this style of fiction could help with the country’s efforts to catch up.

The stories dramatized underdeveloped scientific principles within Chinese society. At the turn of the century, China was unable to compete with neighboring Japan and other Western nations, and even unable to keep foreign interests from influencing domestic policy. Reformers felt that a level of mysticism within Chinese society was an impediment to progress, holding China back from competing with its neighbors.

Science fiction literature, reformers believed, would help inspire Chinese readers to take more of an interest in science and technology, and through a groundswell of support, help push the country forward. The genre, grounded in factual, empirical principles, would further help push China into the future.

Changing world

By the late 1910s, “only members of an older generation of reformers, such as Kang Youwei or Liang Qichao came full circle,” Craig writes, “and appalled by the slaughter of World War I and the evils of Western materialism, advocated a return to traditional Chinese philosophies.”

In the years leading up to the Second World War, the political makeup of the country was changing: leftist political ideals began to take root, and after the 1917 Russian Revolution, Chinese intellectuals began to explore the possibility of bypassing capitalism, which was closely identified with the foreign invaders who had caused so many problems decades earlier.

Uprisings in the 1920s helped a pair of organizations grow rapidly: the China Communist Party (CCP) and the Guomindang Party (GMD). After several years of infighting, the Nanjing regime emerged, which consolidated power from all corners of China, and carried out extensive military and police actions against communist agents. By 1937, the country was at war on two fronts: one against encroaching elements of the CCP, and the other against Japan as that nation sought to consolidate power in the Pacific (the second Sino-Japanese War). China’s government eventually persevered over Japanese forces, but in 1946, the CCP took control of the country through a bloody Civil War that ended three years later.

According to Yan Wu, (translated by Wang Pengfei and Ryan Nichols) in Science Fiction Studies#119, “Until recently, it was generally assumed that very little science fiction was written during the years of the Republic. Recent research has established, however, that a great many sf works were published during this period on a variety of themes, and significant discoveries continue to be made.”

Several science fiction works that emerged from this time were books such as the dystopian and satirical Cat Country by Lao She (pen name for novelist Shu Qingchun). It follows a Chinese traveler who crash lands on Mars, only to discover that it’s entirely inhabited by cat-like people, and that their society is in decline: buildings are falling down, the schools are inadequate, and it isn’t long before there’s a revolution and the country is invaded. The novel has been hailed as a novel that took a stark, satirical look at Chinese society.

Another work published around this time was Under the North Pole by Gu Junzheng in 1940. Working as a school teacher and later an editor and writer, he used his position as a platform from which to popularize science through stories and nonfiction articles that sought to illustrate a scientific point. Although he largely abandoned writing fiction, he was assigned to the China Youth Press and the Committee for the Popularization of Science, two institutions which the SFE noted was influential in bringing the works of authors such as Jules Verne and H.G. Wells to China during this time.

People’s Republic of China

On October 1, 1949, the People’s Republic of China formed after the end of the Chinese Civil War. Its leader, Mao Zedong, brought with him a goal of modernizing the country through a series of reforms that consolidated land and industrial power. His program, Great Leap Forward, echoed the historical movements that sought to advance China technologically and economically in the world. His efforts came at a steep price: an estimated 45 million people died as a result of his policies, a number which climbed higher with the beginning of the Cultural Revolution in 1966.

Because of China’s Communist government’s links to the Soviet Union, translators brought in numerous works from Soviet authors, which, according to the Encyclopedia of Science Fiction, “[shaped] the local sense of what sf should be, particularly along the lines of the Russian calque kepu wenxue, or ‘literature for the popularization of science.’”

The time saw a number of authors publishing stories of their own as well, including Vietnamese author Zheng Wenguang, who moved to China and published “From Earth to Mars,” in 1954, about his adopted country’s first mission to Mars.

Zheng noted that as a distinct literary movement, science fiction, held some appeal to the China’s political parties: “The realism of science fiction is different from the realism of other genres; it is a realism infused with revolutionary idealism because its intended reader is the youth.” In some ways, genre fiction functioned in two roles: continuing the idea of national self-improvement, while also instilling a political and patriotic narrative within China’s youth.

As China advanced into the twentieth century, science fiction authors had to tread carefully with their content for fear of retribution, or of being silenced altogether. One author, Hu Feng, was critical of Mao Zedong’s policies, calling out artwork which he viewed as propaganda: he was sentenced to 25 years in prison for a letter he published.

The emphasis on literature that directly supported a social and political movement persisted in China, and, as a result, dramatically affected the tone and style of all science fiction published during this time. According to The Encyclopedia of Science Fiction, genre arts survived by navigating “a path through this Orwellian minefield by embracing its role as a didactic medium for children. As a result, almost all Chinese sf stories from 1949 until the 1980s were Technothrillers and Edisonades for juvenile readers.”

Furthermore, the Encyclopedia of Science Fiction notes that science fiction was primarily written with the following elements: a setting in the near future, with patriotic scientists solving problems bolstered by their faith in the system, with story lines that were primarily designed to fill some sort of educational role.

“Science literature” was encouraged to help promote a socialistic utopian future, and scholar Mingwei Song noted in China Perspectives, After 1989: The New Wave of Chinese Science Fiction that Chinese science fiction tended to promote utopianism and technological optimism:

“It can be said that from its inception in the late Qing period, Chinese science fiction ‘was instituted mainly as a utopian narrative that projected the political desire for China’s reform into an idealized, technologically more advanced world…While science fiction suffered long periods of inactivity in twentieth century China, the sweeping utopianism remained a guiding force in revivals of the genre after the late Qing.”

This fits hand-in-hand with the genre’s origins as a literature of self-improvement, one that pointed China towards a brighter, better and stronger future.

The original value of the genre had persisted: a style of fiction with an intrinsic purpose beyond mere entertainment: it remained a genre in which China would imagine better and brighter futures for itself.

The Cultural Revolution

In May 1966, Mao urged his supporters, through a series of letters and rallies, to oust anyone opposed to the country’s political direction. Over the course of the summer, counter-revolutionary feelings grew to a fever pitch, leading to the rise of a student paramilitary group known as the Red Guard, which sought to push against ‘intellectual’ and ‘bourgeois’ factions within Chinese society. Supported by Mao, the movement gained steam and began to attack elements and individuals deemed to be working against him.

During the Cultural Revolution, the Red Guard attacked and killed intellectuals and artists, burned their books and destroyed historic sites. Dissidents were sent to ‘reeducation’ camps. Ultimately, Mao was able to consolidate his power.

The Cultural Revolution marked a sudden stop for science fiction in China. In Science Fiction Studies Han Song wrote that “writers were silenced because the genre was regarded as something from corrupt Western culture that could lead people astray.” Cat Country author Lao She, was one such target: his critical look at China’s direction in his novel didn’t go unnoticed, and in 1966, he was singled out and attacked by a mob on August 23. Distraught and humiliated, he drowned himself in Taiping Lake in Beijing.

Zheng Wenguang was also silenced amidst the Cultural Revolution. While he would later resume writing in 1976 after the period ended, his work changed in the aftermath of the Cultural Revolution, with “his generation [adding] some dystopian reflections on Chinese politics into the genre, but their experiment was quickly silenced by the government campaign against ‘spiritual pollution’ in the mid-1980s”, noted by scholar Mingwei Song in China Perspectives. Zheng’s public career ended in the 1980s after a stroke left him paralyzed, and he passed away in 2003.

Rebirth

Mao died in 1976, and with his passing, the Cultural Revolution largely came to an end. His successor, Deng Xiaoping, began to reopen the country by enacting a number of economic reforms and eased governmental controls on its subjects, which had a profound and game-changing impact on the lives of Chinese citizens.

The end of the Cultural Revolution also brought a rebirth of science fiction. An immediate result was the formation of a dedicated genre magazine, Kexue Wenyi (Science Literature and Art), which published its first issue in 1979. The magazine was a state-supported publication until 1984, when it went independent after losing its government funding.

When the magazine relaunched, it became “the nexus of a group of interrelated ventures in book publishing and translation.” The magazine adopted a new name in 1989 Qitan (Amazing Stories) , and again in 1991 as Kehuan Shijie (Science Fiction World) . The magazine did exceptionally well in the 1990s, with circulation peaking at 400,000 subscribers before dropping off to roughly a quarter of that at the present day. Despite that drop, when compared against circulation figures from US genre publications, Science Fiction World is one of the most widely read science fiction publications on the planet.

In China Perspectives, Mingwei Song points to 1989 as the point when science fiction began to blossom full-force in China; it was then that “a new paradigm of science fictional imagination began to complicate, if not deny or be ashamed of, the utopianism that had dominated Chinese politics and intellectual culture for more than a century.” He highlighted Cixin Liu’s first novel China 2185 (which has been posted on the internet, but not formally published in print), in which a student scans Mao’s brain and resurrects him in a virtual environment.

The magazine helped prompt an explosion of new authors working in the field, says Song. Coming of age in a time after the harsh years of the Cultural Revolution, this group of authors were able to take advantage of a less-restricted environment, in which they could imagine China’s futures, and who weren’t bound by the genre’s earlier tendencies for their stories. Some of those authors included Wang Jinkang, who began publishing stories in 1992 after making up and telling stories to his ten-year-old son, and Han Song, an editor at Xinhua News Agency.

Han noted that China has undergone extensive changes in the last couple of decades as its found itself becoming a major world power. That tension is something that he’s worked into his own stories. “To be a journalist in present-day China is like inhabiting a science fiction world,” he says. Those changes lead to considerable cultural anxieties between the tention of western and Chinese ideals:

“Science, technology and modernization are not inherent in Chinese culture. They are like alien entities. If we buy into them, we turn ourselves into monsters, and that’s the only way we can get along with Western notions of progress.”

That tension is one that genre fiction is primed to exploit.

Chinese science fiction today

Ken Liu and Xia Jia have each noted that they’ve heard or been asked a similar question a number of times: how is Chinese science fiction different from ‘regular’ (read: American) science fiction? The answer, they note, is complicated:

“I usually disappoint them by replying that the question is ill defined and there isn’t a neat sound bite for an answer.” Liu wrote.

“Any broad literary classification tied to a culture—especially a culture as in flux and contested as China’s—encompasses all the complexities and contradictions in that culture. Attempts to provide neat answers will only result in broad generalizations that are of little value or stereotypes that reaffirm existing prejudices.”

Jia affirmed with her own answer: “It is true, however, that for the last century or so, ‘Chinese science fiction’ has occupied a rather unique place in the culture and literature of modern China.”

In the past decades, China has found itself rapidly advanced in fields ranging from artificial intelligence to spaceflight capabilities, an environment that’s helped to encourage science fiction writers. It put its first astronaut, Yang Liwei, into space in 2003, landed its first probe on the moon in 2013, and has begun laying the groundwork for its own space station, Tiangong, launching modules into orbit in 2011 and 2016 (they deorbited in 2018 and 2019), with other ambitious plans to reach the Moon and beyond.

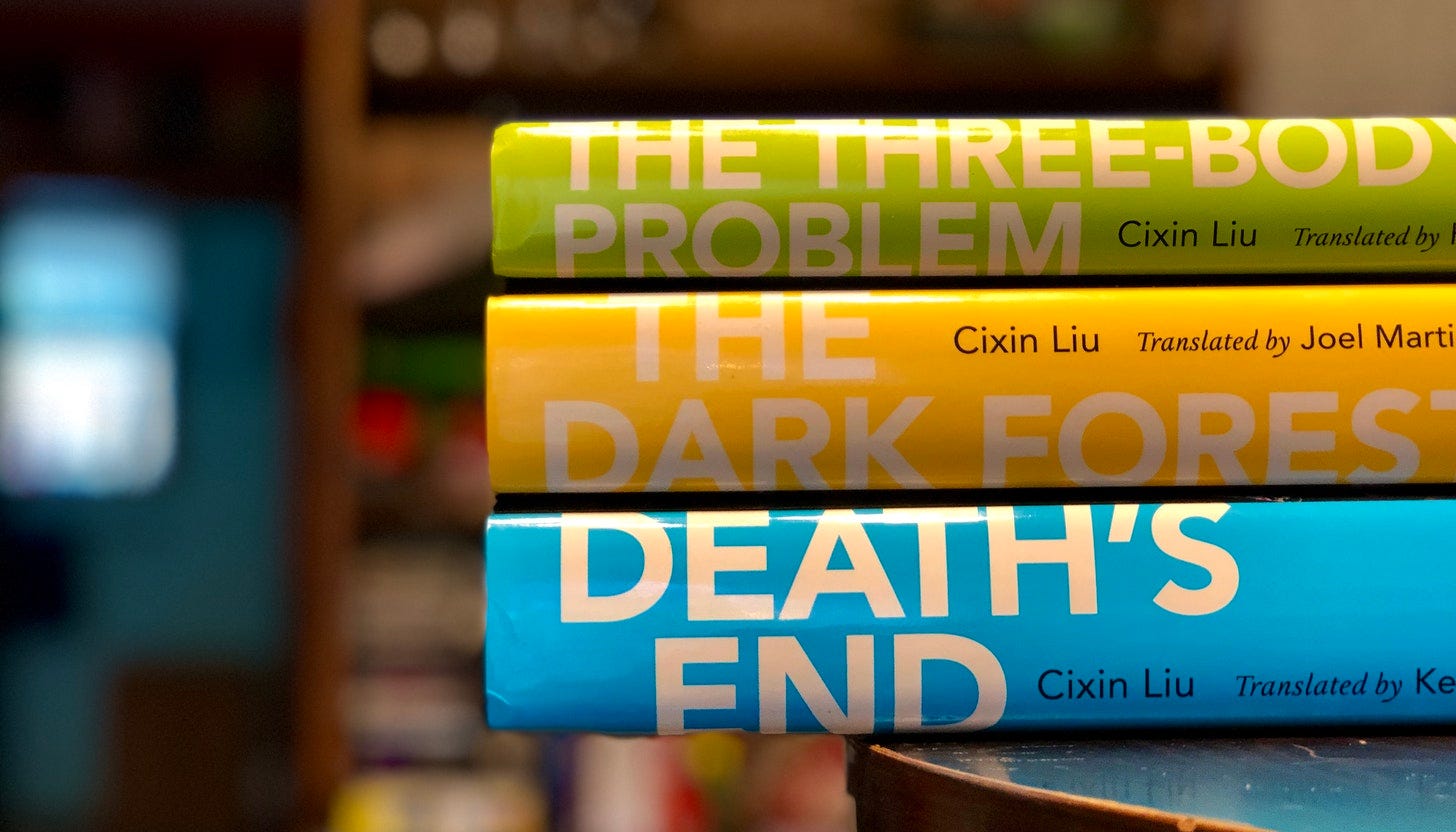

It’s in this environment that Cixin Liu found his greatest success with his Remembrance of Earth’s Past Trilogy. He published the first novel Three-Body as a serial in Science Fiction World and subsequently republished the story in book form in 2008. In 2008, he published a sequel, The Dark Forest, and in 2010, completed the trilogy with Death’s End. Since their publication, Liu has sold half a million copies of each novel, making him one of the country’s foremost popular science fiction authors.

Speaking to The New York Times in 2014, Liu indicated that due to the economic successes China’s had, science fiction has come along with it: “China is on the path of rapid modernization and progress, kind of like the U.S. during the golden age of science fiction in the ’30s to the ’60s. The future in the people’s eyes is full of attractions, temptations and hope. But at the same time, it is also full of threats and challenges. That makes for very fertile soil.”

Not all of China’s science fiction derives from technological advances and technological optimism, however. One notable example is Chan Koonchun’s novel The Fat Years, in which February 2011 ceases to exist for the country: people can’t remember what happened, and all official records are non-existent. Writing for the LA Times, Clarissa Sebag-Montefiore noted that “insecurity over China’s meteoric economic growth coupled with an authoritarian leadership has produced ripe pickings for the genre’s top writers.” Koonchung’s novel, a heavily political critique of the country’s leadership, has since been banned from publication within China, and was translated into English in 2011.

The success of Liu’s novels have had an enormous impact on Chinese readers. Liu observed that the novel has captured the attention of an enormous segment of China’s reading public, from students to professionals and to scientists, who have in turn created social media parodies, fake trailers and have otherwise turned awareness of the book into a popular meme that’s widely understood.

But while China had a vibrant science fiction scene, those stories didn’t make their way to English readers. That changed when a Chinese publisher decided to see if English readers would be interested in Liu’s trilogy. China’s Educational Publications Import & Export Corp. commissioned Ken Liu and Joel Martinsen to translate the novels into English. A translation is an expensive proposition: it requires a publisher to bring in someone to reinterpret the book into a new language, and represents a high barrier for authors trying to reach new markets.

On io9, Liu noted that translation goes beyond simple word replacement: translators must find ways to interpret an entire culture in another language:

“Modern translation scholars are increasingly shifting their attention from the mechanical aspects of linguistic manipulation to deeper analysis of translation as cultural performance. When the cultures being mediated by the translator are very distant from each other, the translator must take audacious, bold steps to bridge the gap.”

This had long been done with the translated Chinese science fiction that had been published throughout China, but it hadn’t been done often going in the other direction. If done properly, a translation does more than provide a foreign-language reader with a new story: it introduces them to the culture of a foreign land.

Liu, who was born in Lanzhou, China at the tail end of the Cultural Revolution in 1976, grew up in the United States and began publishing science fiction and fantasy stories in 2002. In 2012, he earned the Hugo, Nebula and World Fantasy awards for his short story ‘The Paper Menagerie’, originally published in The Magazine Of Fantasy and Science Fiction in 2011 (since republished at io9, which put him on the map as a writer to watch). Since the start of his career, he’s published hundreds of short stories in a variety of publications, including Clarkesworld Magazine, Lightspeed Magazine, Asimov’s, and Analog, among others.

The efforts paid off: The Three-Body Problem was met with immediate success in the United States, where it earned praise from genre and national publications such as the Wall Street Journal, New York Times and National Public Radio. President Barack Obama and Facebook CEO Mark Zuckerberg praised the novel.

In 2015, it was honored with the Nebula Award for Best Novel, and later, with the Hugo Award for the same. It was the first time an Asian author had won the award. In an interview with Locus Magazine, Ken Liu wrote about the popularity that the novels enjoy, and the impact of the Three-Body Problems’s Hugo and Nebula nominations in China:

Some reporters asked me, ‘Why are Chinese readers so excited about the Nebula Award? American fans wouldn’t be so excited if one of their books was translated into Chinese and won some award.’ I said, ‘You wouldn’t care. You’re coming from the modern Rome, the core of world culture, whereas China is at the periphery. For Chinese fans, something they love in their language is being recognized by readers in America, who are perceived as the prestige readers.’ One of the aspects of being from a prestigious culture is that you don’t necessarily perceive yourself as having power.”

Other science fiction publications have begun to make a concerted effort to translate the works of other authors from China: publications such as Clarkesworld and Lightspeed have each published their share of translated fiction — not just from China, but from other countries as well.

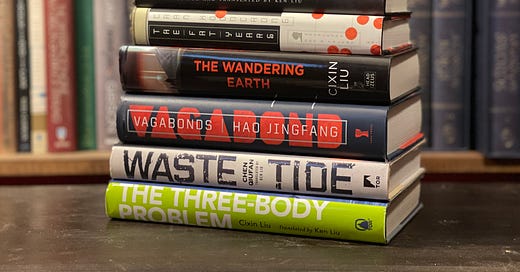

The success of Liu’s trilogy has led to other translations for English readers: Tor published Chen Qiufan’s novel Waste Tide in 2019, while Saga published Hao Jingfan’s book Vagabonds, both with Liu translating. Liu has published other novels, like Supernova Era and collected his short stories in To Hold Up The Sky, while writer Baoshu published his tie-in to Liu’s Remembrance of Earth’s Past trilogy, The Redemption of Time.

The influx of Chinese science fiction into the United States and other parts of the world isn’t limited just to literature. After its success in China, Netflix brought in Chinese SF blockbuster The Wandering Earth to its platform in 2019, and recently debuted a Korean SF blockbuster, Space Sweepers. Late last year, Netflix doubled down: it announced that it had picked up the rights to adapt the Three-Body Problem for a series, with the creators of Game of Thrones leading the project.

The future

So, what does the future hold for the state of Chinese science fiction? The answer is complicated. China has continued to grow under President Xi Jingping, pushing forward in various scientific and technological fields.

The country has experienced a huge amount of growth in the last couple of decades, with its population catapulting into the middle class, leading to new spending power and economic opportunity. Online platforms have lead to sprawling fanbases for authors like Liu, and given new authors space to write about the future.

But as China’s grown, it’s experienced new problems. It’s experienced issues with its neighbors as it works to assert its authority in its regional sphere, it’s rounded up its citizens for reeducation camps in the Xinjiang Uyghur Autonomous Region (support of which has landed Cixin Liu in PR trouble), and cracked down on free speech and expression within the country. Authors that I’ve spoken to have noted that this has led to a bit of a chilling effect on publishing as more emphasis is placed on on patriotism and adhering to the country’s political messaging.

But as China’s grown into the world, it’s broken down some of the barriers that have kept its authors from reaching wider, global audiences, bringing readers around the world new worlds and perspectives. Despite some of the challenges that they face, authors will continue to write science fiction for magazines, books, online platforms, and abroad, all imagining what the future of their country might look like in the decades to come, on Earth, and in the depths of space.