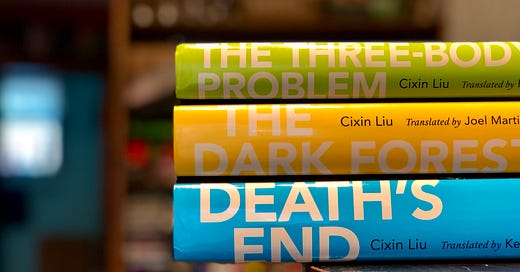

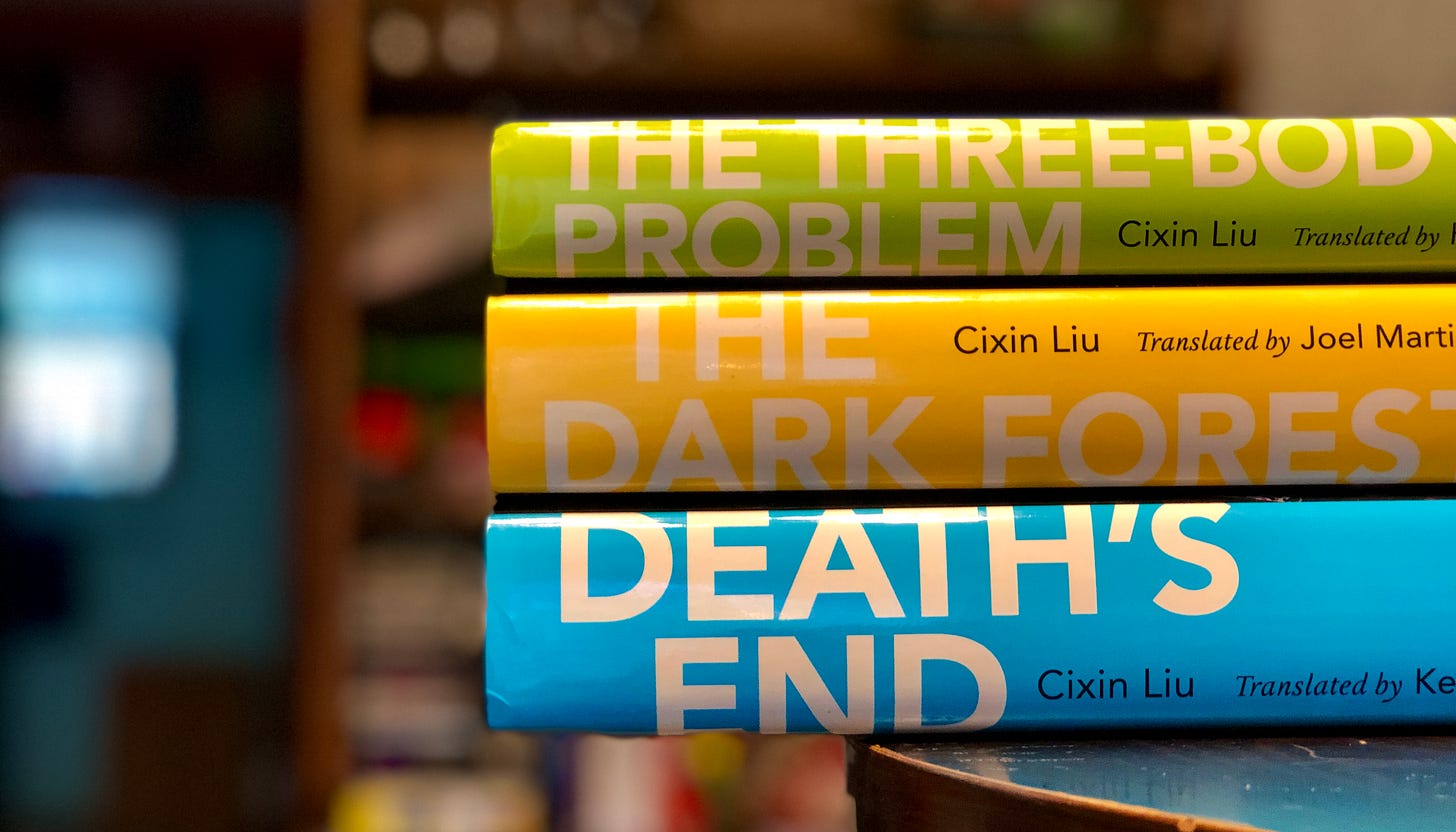

Yesterday, five US senators, Marsha Blackburn (R-TN), Rick Scott (R-FL), Kevin Cramer (R-ND), Thom Tillis (NC), and Martha McSally (R-TX) sent a letter to Netflix Chief Content Officer Ted Sarandos over a recent project that the streaming company announced: an adaptation of Liu Cixin’s Three-Body Problem.

In the letter, they write:

The Chinese Communist Party (CCP) is committing atrocities in the Xinjiang Uyghur Autonomous Region (XUAR), also known as East Turkistan to locals, including mass imprisonment, forced labor, thought transformation in order to denounce religion and culture, involuntary medical testing, and forced sterilization and abortion. These crimes are committed systemically and at a scale which may warrant a distinction of genocide. Sadly, a number of U.S. companies continue to either actively or tacitly allow the normalization of, or apologism for, these crimes. The decision to produce an adaptation of Mr. Liu’s work can be viewed as such normalization.

Liu has made some statements about this: in a profile for The New Yorker published last year, staff writer Jiayang Fan asked about the well-documented atrocities, to which he said: “Would you rather that they be hacking away at bodies at train stations and schools in terrorist attacks? If anything, the government is helping their economy and trying to lift them out of poverty.”

China’s government has said that they’re conducting a counter-terror and deradicalization campaign, and Liu’s answers feel as though they’re right in line with the talking points from China’s communist party.

Further Reading on this subject: Witness to discrimination: Confessions of a Han Chinese from Xinjiang

His reply to the question raised some eyebrows within the fan community, from outright condemnation to some more nuanced discussion: Liu isn’t a governmental representative and isn’t exactly in the best of positions to speak on its behalf. He was put in a difficult position with that interview. Deviating from the party line seems as though it would bring some extreme risks to his personal safety, and I can’t help but wonder if there was any other answer that he could actually give without the potential of swift repercussions. Reading the trilogy, I can’t imagine that Liu would be in favor of these sorts of internment camps — his books feature such imagery, looking back on the Chinese cultural revolution and later when (SPOILERS!) the Trisolarans arrive on Earth and subjugate humanity.

Word of this seems to have percolated up to the five GOP senators behind the letter: with a series of passive-aggressive questions, they ask Netflix if it agrees with China’s policies, if they were aware of Liu’s statements, and what they’ll be doing about it moving forward.

Netflix’s lawyers will undoubtably come up with a response with a statement about their values and so forth, and ultimately, I don’t see this as anything other than a handful of senators doing some busy work, rather than anything of substantiative policy.

September 26th Update: Netflix responded to the letter (via TheWrap), saying, among other things, that “Mr. Liu is the author of the books, not the creator of this series,” and that his views aren’t “reflective of the views of Netflix or of the show’s creators, nor are they part of the plot or themes of the show.” They also note that they judge the projects on their individual merits, rather than those of the original creators.

But that’s not to say that they’re not asking the right questions, and whether or not Netflix should keep these atrocities in mind as they move forward with the project.

China has been a growing market for Hollywood films: it has a rising middle class, which means, among other things, rising incomes and the time to participate in recreational activities like going to the movies. The country has seen its number of theaters skyrocket, and along with it, a burgeoning film industry. When US films are allowed in, access to that market can mean additional hundreds of millions of dollars for a studio. US films can be edited for their content to pass Chinese censors — Vanity Fair has a decent rundown of the various ways that studios have altered films for that purpose. One of the most blatant examples is Iron Man 3, which featured additional scene set in China and featuring Chinese actors and actresses. There are other examples of Chinese - US collaborations, like 2017’s The Great Wall, in which a handful of soldiers and Matt Damon fight monsters.

On the other side, China’s been beefing up its movie industry. Last year, it released The Wandering Earth (based on a story from Liu), the country’s first big homegrown SF film, which was wildly successful domestically. It had a limited theatrical run here in the US (I drove down to Boston to see it — it was a lot of fun to see on the be big screen amidst a Chinese audience), and it eventually found a streaming home on Netflix.

On one hand, Netflix could be blundering into a PR nightmare with the project. We’ve seen this recently with Disney and its recent live-action adaptation of Mulan. As the film entered the streaming space on Disney + earlier this month, viewers noted that a handful of governmental agencies from Xinjiang were thanked — some of the footage from the film was apparently shot there. The inclusion prompted a hefty backlash against the film, although that doesn’t seem to have translated into a financial hit for the company.

On the other hand, the senators do have a point: there are real atrocities taking place in China, and it’s a problem that you can easily overlook if you happen to like the movie that you’re watching, or enjoy the book that you’ve read. Netflix should take this into consideration as it moves forward with the project, because essentially, China is counting on that normalization to allow it to move forward with its plans and policies. That’s sort of been a trademark of how it handles these issues, whether that’s extending its reach into the South Pacific, angering its neighbors, or extending an economic and military arm into Africa and the Middle East.

Moreover, there seems to be a concern on the part of US policymakers that the exportation of Chinese art and culture is intrinsically designed as a way to endear the country to the world. There’s elements of this that you can see: tourist visits to the Great Wall of China, the lending of Panda Bears, and the publication of Chinese authors like Liu and others.

To be clear, this might be a legitimate concern: China certainly has global ambitions, and as its stature in the world has risen, its leaders want to present a certain, palatable image of itself to the rest of the world. Mind, I don’t think that’s the case when it comes to books like Liu’s The Three-Body Problem, or any of the stories that you see in Clarkesworld Magazine or others. There’s a tendency to oversimplify the actions of Chinese officials and bodies — just look at the stories of how the country had “banned” time travel stories, for example — but these are complicated systems at work: they’re individuals with complicated feelings, opinions, and rationalizations.

There’s also a tendency to overthink or misrepresent what these authors are trying to say. In a recent opinion piece for The Boston Globe, Niall Ferguson interpreted the book as China creating a global problem that it then exploits to its own benefit: inviting the Trisolarans to invade, and then saving the world. “It’s OK for China to cause a global disaster in order to safe the world,” he writes.

At best, that’s just poor reading comprehension. At worst, it’s deliberate misinterpretation to try and prove a point. (In this case, he’s trying to link that argument to COVID-19.) Ken Liu has often said that there’s no catch-all categorization that distinguishes Chinese SF from its other global counterparts. “Any broad literary classification tied to a culture—especially a culture as in flux and as contested as contemporary China’s—encompasses all the complexities and contradictions in that culture,” he wrote in “China Dreams”, the introduction to Invisible Planets: An Anthology of Contemporary Chinese SF in Translation. “Attempts to provide near answers will only result in broad generalizations that are of little value, or stereotypes that reaffirm existing prejudices.”

That takes us back to the letter at hand. Certainly, media and content companies have some responsibility to make sure that their actions and productions aren’t causing harm. But it’s worth recognizing the complexity of the situation: Liu certainly could support his government’s actions, but it seems just as likely that there’s only one answer that he could safely provide. A superficial and deliberate misinterpretation on the part of US officials doesn’t feel like a way to do anything other than try to make noise about an issue in the midst of a contentious election year.

Ultimately, I think it’s worth looking at the spirit of the books in question: if Liu has a dominating theme, it’s that people, when working together, can accomplish great things, like explore the universe or safe the planet from harm. In interviews, he’s spoke about how the human spirit transcends borders and that if we solve our differences, we can move forward in some great directions.

That’s a message that I think people around the world could stand to take to heart.

Thanks for reading. I’m headed back outside to finish refurbishing my decrepit garage. I’ll be back with another letter in the nearish future. In the meantime, let me know your thoughts!

Andrew