Wordplay: how (and what) I'm reading, Chinese science fiction, and hints of things to come

Greetings!

This is letter #2 (you can read the first here). Thanks for those who told me that they liked the first letter, or who have since signed up or spread the word. It's much appreciated. This week, I've got some thoughts on how I read, Chinese science fiction, and some other assorted things.

How the hell do you read so much?

This is a question that I get pretty frequently, usually because I've posted a picture of a stack of book that I've gotten in the mail. I frequently have 4-5 books going at any given time, and I've found Goodreads to be useful with tracking and remembering what I'm reading. Usually, I'll start a couple of books at once, and see which one catches me first out of that pack, and go from there.

But the last couple of years, I've been falling behind my generally-stated goal of 52 books (a book a week) a year. This year, I decided that I just needed to buckle down and make time. I'd been fitting reading time in whenever I was finding it, but I flipped that around this year, and set aside dedicated time in the morning to sink into a book. My goal is to read 50 pages or to hit 9 AM, whichever comes first. And, it works. Sitting down to actually read also has the added advantage of actually absorbing what I'm reading, especially when it's not at 5-minute bursts at a time. So far, I'm up to 64 books this year, well above my goal.

There is a personal pride element to this: I like to read, and there's so many books that I don't get to. But there's other things at play here. I'm a firm advocate for what reading does do your mind, and that it's an incredibly important skill for anyone to use. It helps your critical thinking skills, allows you to empathize with others, and helps impart and convey skills and ideas that you might not get anywhere else, especially when you're just reading online. There's been a general push in the military and the business world for people to pick up books more often, especially as we find ourselves looking at our phones or screens more and more. So, dear readers, I'd challenge you to figure out some part of your day and block it off: protect that period of time, set the phone down, and read something. (Seriously, go do it!)

This doesn't necessarily translate into stuff that I review. Most of the books that I get in the mail end up going un-read, simply because it's an overwhelming amount. I'll sort out what looks interesting for the site and what I'm interested in personally, and will sort out what I get into piles for the book lists that I publish on The Verge, and I get through that little by little. The ones I don't read end up with friends or one of two local libraries, and the ones that I *want* to read end up on another shelf, which I have to pick through a couple of times to purge when it gets full. There's... a lot that comes out, and not nearly enough hours to check everything out.

Beyond novels, I've been making an effort to read more short fiction, something I've fallen woefully behind on in recent years. I've been fitting these stories in when I can get to them, but the short length means that that's much easier, while the variety of platforms means that I can get to them on a variety of devices, like my iPad, phone, or computer. I have been making it a point to subscribe and purchase physical issues, though — I've been finding copies of Asimov's Science Fiction and The Magazine Fantasy & Science Fiction at my local Barnes and Noble, while I support Clarkesworld Magazine via Patreon.

Chinese Science Fiction

I feel like I've been talking a lot about Chinese science fiction lately. There's a good reason for that: I'm writing a longer piece on the subject, and there's just a lot to talk about. I blew through Cixin Liu's Three-Body trilogy this fall, and then reviewed his latest book, Ball Lightning. I also revealed the cover for a tie-in novel to his trilogy, The Redemption of Time, written by Baoshu. I also wrote about an upcoming film based on one of his stories, The Wandering Earth.

Chinese SF is going to be pretty exciting in the 2019 as well. Clarkesworld has been steadily publishing a whole bunch of short stories and novellas from the country, and we're going to see a bunch of new books hitting shelves: Ken Liu has a new anthology coming called Broken Stars: Contemporary Chinese Science Fiction in Translation, Chen Quifan's The Waste Tide (translated by Ken) comes in April, the aforementioned Redemption of Time in July, and far out in September, there's Hao Jingfang's Vagabond, although I've been told that that will very likely be pushed back.

So why the flood in the last couple of years? Certainly, Cixin winning the Hugo Award for Best Novel in 2015 helped — it gained out-sized attention in the media (way beyond the usual coverage), but there was already attention bubbling up ahead of time. China has been seeing a pretty fast growth in its own science fiction scene, and publishers and exporters recognize that there's a huge Western audience. The Three-Body Problem is a book that checks all of the right boxes for traditionalist readers who want big ideas, lots of science and physics, and the entire trilogy does deliver that nicely.

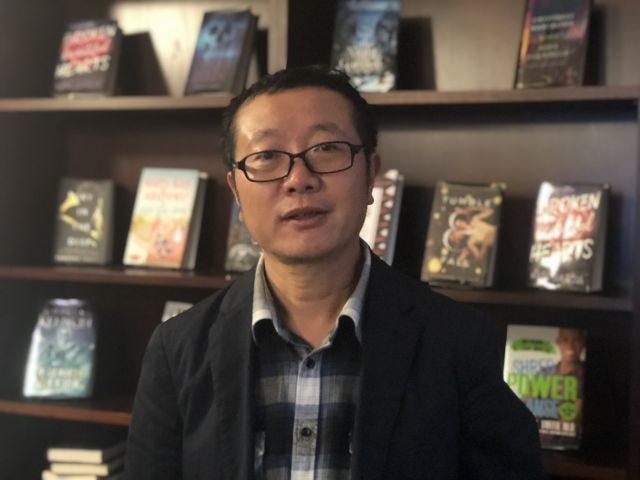

Earlier this week, I got to meet Cixin Liu in New York City, and it was a delight to meet him. Tor arranged for a translator, because he doesn't speak very much English, but he was friendly, and I was able to ask him a bunch of questions that got some interesting answers. That will get worked into this feature, and I might end up publishing it as a standalone interview at some point.

One of the biggest questions that keeps coming up is: what are the differences between Chinese SF and US SF. I had to ask it, but that question is kind of a dumb one: every author is different in both traditions, so there's no one thing that really stands out as a defining factor between each. I get the sense that he's been asked the question quite a bit, but I think that while there are differences, there's more that's similar.

My running theory is that science fiction is an outgrowth of industrialization and / or massive technological change: people are grappling with the problems and changes that technology brings. China has a long history of science fiction, where it was purposefully utilized to support science education. Liu confirmed this in my chat with him, but noted that during the cultural revolution, science fiction essentially withered on the vine, and it wasn't until the 1980s and 1990s that it began to make a comeback, in part because relations between the PRC and US began to thaw a bit. There's a bit of a resurgence because the country is undergoing some pretty incredible changes now.

Another thing that he mentioned that stuck with me was that science fiction "was the literature for the masses." This is something that I've seen in other places, and part of the reason for why I've been drawn to translated SF — not just from China, but from other places around the world, like Russia, Cuba, Spain, and other countries. The world is a big and scary place — China, Russia, and the US have no shortage of tensions right now — meaning that finding points of a cultural middle ground are all the more important. Not necessarily to agree or compromise one's values, but to understand and empathize where people are coming from. Think of it like studying abroad — something every student should do! — for your mind.

I'd certainly recommend Liu's Three-Body trilogy to anyone who hasn't read it yet, but if you're looking for other translations to check out, there's plenty to choose from — The Sacred Era by Takayuki Tatasumi, translated by Baryon Tensor Posadas (Japan), Gene Mapper and Orbital Cloud by Taiyo Fuji, translated by Jim Hubbart and Timothy Silver, respectively (Japan), Solaris by Stanislaw Lem, translated by Joanna Kilmartin and Steve Cox (Poland), Frankenstein in Baghdad by Ahmed Saadawi, translated by Jonathan Wright (Iraq), Roadside Picnic by Arkady and Boris Strugatsky (translated by Olena Bormashenko (Russia), and A Planet for Rent by Yoss, translated by David Frye (Cuba). A couple of anthologies I've come across are Red Star Tales: A Century of Russian and Soviet Science Fiction, edited by Yvonne Howell (Russia), and Invisible Planets: Contemporary , edited by Ken Liu (China).

My reading list

As noted in my previous letter, I was reading Kim Stanley Robinson's Red Moon, and last week, I published my review. It's not a bad book, but it was a disappointment. He discusses quite a few neat ideas, but the book as a whole is hampered by characters that just don't bring them together. Ah, well.

Another book I finished up was Becky Chambers' Record of a Spaceborn Few. I have some longer thoughts that I'll unpack about it later (maybe the next newsletter?), but it's a fantastic read, and if you haven't read her other books, A Long Way to a Small, Angry Planet and A Closed and Common Orbit, you should. They're incredibly empathetic, beautiful reads about people, and they take on a very optimistic view of the world.

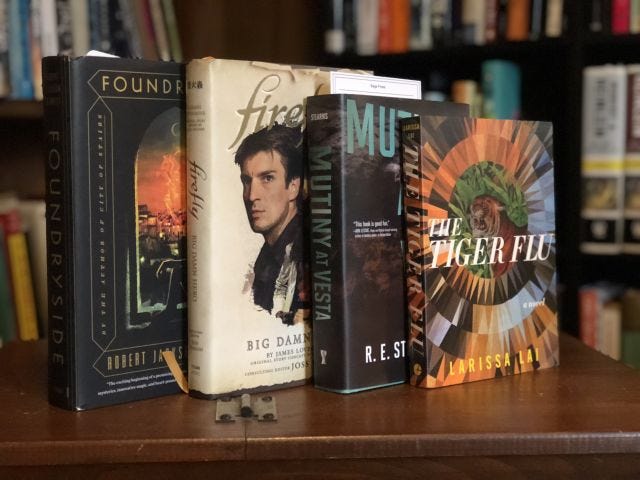

Other things I'm reading: getting back to Foundryside by Robert Bennett Jackson and R.E. Stearns' Mutiny at Vesta, but I've also picked up James Lovegrove's upcoming Firefly novel, Big Damn Hero, and I'm interested in seeing what this does for the franchise. There's a bunch of others, but these are on the immediate top-of-the-list. What'll end up as a review? We'll see how fast I get through this batch.

Some upcoming stuff

There are a couple of cool projects and longer features that I'm involved in that are coming up. I can't talk about, well, any of them just yet, but they'll hopefully be coming soon. There's a larger project that ... I can't talk about it just yet, but stay tuned next Wednesday. It's super cool, and I'm very proud to have been part of it.

Another project ... I don't yet know when I can say anything, but it's even cooler, and I can't wait to unveil it. Stay tuned.

That's it for this letter. Thanks again for reading, and for folks who have written in about it, I really do appreciate it! If you liked it, forward it along or tell a friend.

Andrew