Hello there!

I hope that the new year is treating you well. I’ve been hard at work on a bunch of things while fighting off a head cold.

I’ve got a couple of things here to chat about this time around: a look at Tamyn Muir’s fantastic novel Gideon the Ninth, Apple TV’s For All Mankind, another book recommendation I missed last letter, Hugo eligibility / recommendations, and an update on The Book.

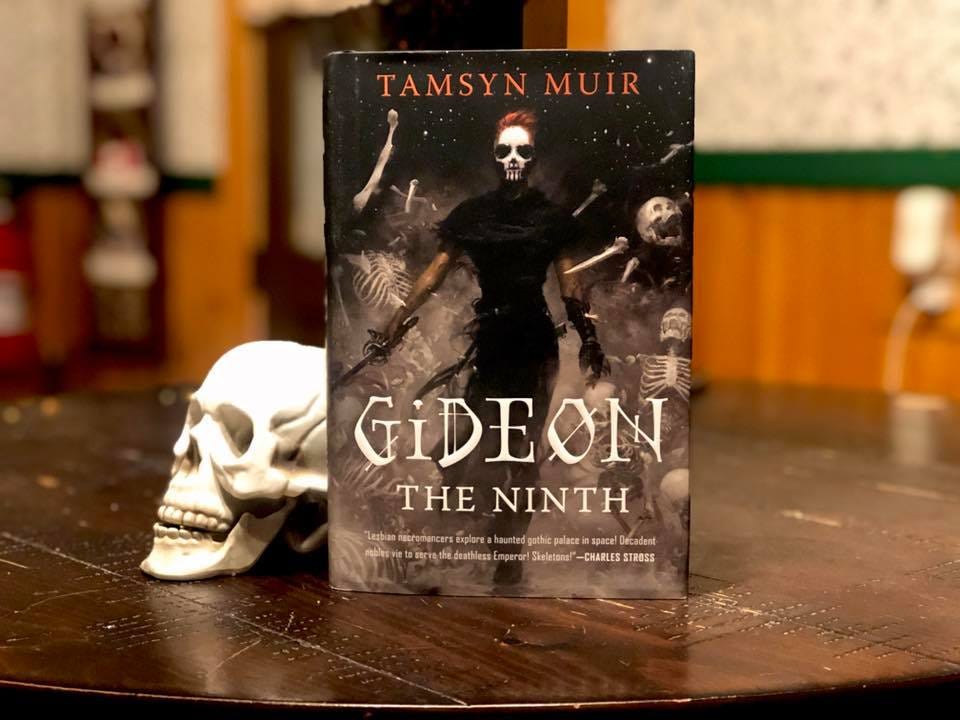

Necromancers in Space: Tamsyn Muir’s Gideon the Ninth

One of my favorite books of 2019 was Tamsyn Muir’s debut, Gideon the Ninth. I’d finished enough of it to include it on my best-of-the-year list, but I’d gotten sidetracked to the point where I didn’t get to finish it until a couple of days ago.

The short version: this book is a gothicy riot, and you should read it for the dialog and interplay between Gideon and Harrowhawk alone.

Longer version: set in weird, pulpy world, the novel follows Gideon, an orphaned swordswoman who’s been raised in the grim Ninth House alongside necromancer Harrowhark Nonagesimus, the house’s Reverend Daughter. Gideon desperately wants to leave, and has tried to escape on a number of occasions: she’s led a lonely and dismal life within the house’s gloomy walls while being trained to become one of the Ninth’s soldiers. When the Emperor issues a challenge to all of the houses in his realm, Harrowhawk journeys to the First House to complete a set of challenges to become a Lyctor, with Gideon accompanying her as her Cavalier. Problems ensue.

What plays out is essentially a locked-room mystery set in a gothic haunted house… in space. It’s a small adventure within a much larger world, with extremely high stakes that become readily apparent as the book progresses.

But all of that is in the background as Muir focuses on her characters. Gideon and Harrowhawk hate one another. Gideon because of her life-long treatment from the members of Ninth House, and Harrowhawk, for reasons that become apparent later on. As the two complete a series of challenges in the house, they’re forced to put aside their differences and work together.

But what I loved the most about this novel was the wordplay and antagonistic relationship between Harrowhawk and Gideon. They’re a delight every time they’re together: Gideon for her sharp-as-a-tack sarcasm and wit, Harrowhawk for her focus and condescension. They work magnificently together, and the emotional arc of their relationship is fun and more than a little heartbreaking.

Essentially, the book is a pulpy science-fantasy that could have come straight out of the C.L. Moore era of Weird Tales, coupled with a buddy-cop comedy that includes plenty of skeletons. It’s a fun read, one with plenty of action and drama as Muir introduces readers to the various members of the houses, and as she peels back the curtain a bit more on the world.

Then, there’s the dialogue: what fantastic wordplay!

“Harrow,” said Gideon, finding her tongue, “don’t say these things to me. I still have a million reasons to be mad at you. It’s hard to do that and worry that you’ve got brain injured.”

I’m merely saying you’re an incredible swordswoman,” said the necromancer briskly. “You’re still a dreadful human being.”

And:

Aiglamene had found and reforged the sword of Ortus’s grandmother’s mother, and presented it to a nonplused Gideon. The blade was black meta, and it had a plain black guard and hilt, unlike the intricate messes of teeth and wires that adorned some of the other rapiers down at the monument. “Oh, this is boring,” Gideon had said in disappointment. “I wanted oen with a skull puking another, smaller skull, and other skulls flying all around. But tasteful, you know?”

And:

Gideon marveled that someone could live in the universe only seventeen years and yet wear black and sneer with such ancient self-assurance.

And:

“Too many words,” said Gideon confidentially. “How about these: One flesh, one end, bitch.”

You get the idea. The book is loaded with lines like this, and it’s worth picking up the audiobook, because narrator Moira Quirk is phenomenal.

What I appreciated about this is that the book could have been played out like a grimdark read, one that’s black, and gothic, and depressing. Muir’s dialogue lifts the novel out of that trap — the stakes are still intact, but she breaks out of the smothering darkness with her humor. It’s not what I’d call a comedic novel (it’s not like Catherynne Valente’s Space Opera), but it’s funny, even while the stakes grow higher and higher.

For All Mankind: Apollo 13 meets The Martian

Over the holiday break, I finally made some time to finish binging Apple TV +’s science fiction series For All Mankind, an alternate history of the space race in which the Soviet Union lands first, which results in a prolonged space race. The United States doesn’t want to be left behind, and continues beyond Apollo 17, setting up a lunar base. I wrote about the first handful of episodes for Polygon back in November, saying that it’s a revisionist take on the history behind the space race, even when it’s rocky at a couple of points.

Some spoilers ahead for the entire series.

That’s pretty much my baseline expectation with any first season of any TV series: showrunners, actors, and writers are throwing some darts at a dartboard to see what beats land solidly. In the first half of the series, we’re introduced to the basic premise, and that to staff up, NASA begins recruiting female astronauts, and by the fifth episode, they establish a lunar base to mine ice in the Lunar south pole.

With that established, the show finally kicks into gear: with its base established, NASA starts to conduct mining operations within three years, sending up a team of astronauts to crew the base. It turn out that keeping such a base occupied is challenging in and of itself, and the final five episodes make a bit of a mini-arc surrounding the problems at Jameson Base in 1974.

Right as things seem to start going well for the US, everything goes downhill quickly. The Apollo 23 mission blows up on the launchpad, killing a number of the support staff, including Gene Kranz. The disaster sets NASA back: the mission was to resupply and relieve the crew on the Moon, leaving Gordo Stevens (Michael Dorman), Danielle Poole (Krys Marshall), and Ed Baldwin (Joel Kinnaman) stranded for an extended period of time. They can’t just pack up and leave, either: the Russians have established their own base not far away, and the moment they take off, they’d essentially cede the base to them.

That extended mission takes its toll. Gordo experiences a mental break, and has to be subdued. To give him some cover and to allow him to save face, Danielle deliberately breaks her arm, necessitating a return home, leaving Ed behind.

Meanwhile, the relief mission isn’t anywhere in sight. A long investigation into the accident uncovers some political kickbacks that led to quality lapses in the hardware, and it takes time to manufacture and fix the parts. Ed has to deal with being on his own, and while he’s up there, his son Shane is killed in an accident. He doesn’t take the news well, and essentially turns off the radio.

The final couple of episodes draw more than a little from the likes of Apollo 13 and The Martian when NASA finally launches a relief mission with Apollo 24. But more problems crop up: the rocket doesn’t fire when in orbit, leaving the astronauts stranded, necessitating an additional rescue mission with the Apollo 25 crew. When the rocket does fire, one astronaut is killed, and NASA scrambles to save both crews.

The series is a solid one, if a bit overpacked and rushed at times. It’s definitely one I enjoyed blowing through in one or two sittings, but the week-to-week format works nicely. It’s weird — The Mandalorian blew up in part by holding a lot back and making people watch an episode a week. For All Mankind sort of… vanished from everyone’s radar, which is a shame: it’s a fun story, and one that sets up quite a bit for Season 2. (The post-credit scene looks as though it’s jumping a decade to the 1980s).

At the heart of the series is a central conceit, one that’s been uttered by scientists and space enthusiasts since the Apollo missions: Space is dangerous, but there’s no greater adventure and worthwhile pursuit for humanity. It’s a message that’s echoed in other space dramas, such as Apollo 13 and The Martian, and one that films like Gravity have pushed back on.

Given that the first half of the series worked to deconstruct the mythos of the space race, I’m a little surprised that it went back to rely on that. The idea that we’re destined to go to space and explore new worlds beyond our own is something that’s definitely embedded in science fiction’s genome, but the show had pushed back on some of that mythology by pointing out that some of the Apollo program’s architects were members of the Nazi party and that NASA was horribly racist and sexist when it come to its astronaut selection process. The show seems to hand-wave those problems aside, as if to say that ‘yes, they were an issue, but the end goal, human habitation in space is still a worthwhile one.’

I don’t disagree with that, but it’s a mythology that’s far more complicated. Space isn’t an inevitability, and it’s a dangerous place for which we’re really not suited for living in. Hopefully, the series will play with that idea a bit more in the second season.

My other, nit-picky criticism for the series? The lunar astronauts and cosmonaut are waaaaaaaaay too clean for extended surface time.

C’mon, costume department. Dirty up those suits!

The Book

The book is moving along nicely. Earlier this week, Iris went off to daycare for the first time (how is she 3 months old already?!) which is giving me plenty of time to write. Suddenly, hitting my base word count (as well as regular news writing for Tor.com and other places) isn’t a struggle, which is nice.

Right now, I’m working on a couple of different tracks: the history of halloween (and weirdly, Thanksgiving?), a look at a major mask studio, and the shifting culture between internet forums and social media platforms.

As of now, my draft has passed the 30k word mark, and I’m happy with what I’ve got so far. There’s still a good chunk left to go, but now that a majority of the interviews are done, the rest should fall into place nicely.

Another Anticipated Novel

There’s one book that I forgot to put on my anticipated list for 2020 in my last newsletter: Burn In: A Novel of the Real Robotic Revolution by P.W. Singer and August Cole. I’m a big fan of their novel Ghost Fleet: A Novel of the Next World War, and they’re now turning their attention to robotics and artificial intelligence. It follows an FBI agent who’s tasked with field testing a police robot, and who stumble upon a larger conspiracy. It comes out on May 26th.

Hugo Nominations & Eligibility

CoNZealand has announced that nomination for the 2020 Hugo Award are now live!

There are a couple of things that I can point to for eligibility:

Reading List, eligible for Fanzine.

Myself, for Fan Writer, for my work here, and elsewhere in 2019.

Better Worlds. The individual stories here can be nominated in a pair of categories: Short Story, and Dramatic Short Form. All of the stories here are worthy, IMO: A Theory of Flight by Justina Ireland, Online Reunion by Leigh Alexander, A Model Dog by John Scalzi, Monsters Come Howling in Their Season by Cadwell Turnbull, St. Juju by Rivers Solomon, The Burn by Peter Tieryas, A Sun Will Always Sing by Karin Lowachee, Skin City by Kelly Robson, Move the World by Carla Speed McNeil, Overlay by Elizabeth Bonesteel, and Machine of Loving Grace by Katherine Cross.

A Theory of Flight, A Model Dog, St. Juju, A Sun Will Always Sing, and Overlay each got video adaptations, while Online Reunion, Monsters Come Howling in Their Season, The Burn, Skin City, and Machine of Loving Grace all got audio adaptations. Move the World was the only one that wasn’t adapted. I can’t stress how good these adaptations are — the videos are gorgeous, and the audio is phenomenally done. The respective teams on them went above and beyond on this project.

When it comes to recommendations for various works, here’s what I’ll be putting on my ballot:

Short Fiction

The aforementioned Better Worlds short stories — A Sun Will Always Sing, Monsters Come Howling in Their Season, A Theory of Flight are probably my absolute favorites.

Thoughts and Prayers by Ken Liu.

Articulated Restraint by Mary Robinette Kowal.

A Full Life by Paolo Bacigalupi.

Search History for Elspeth Adair, Age 11 by Aimee Picchi.

Novels

Famous Men Who Never Lived by K. Chess

The Ten Thousand Doors of January by Alix E. Harrow

The Light Brigade by Kameron Hurley

A Memory Called Empire by Arkady Martine

Magic for Liars by Sarah Gailey

The Lesson by Cadwell Turnbull

The Future of Another Timeline by Annalee Newitz

The City in the Middle of the Night by Charlie Jane Anders

Related Work

Becoming Superman: My Journey from Poverty to Hollywood by J. Michael Straczynski

The Moon by Oliver Morton

It’s All Just A Draft by Tobias S. Buckell

Monster, She Wrote: The Women Who Pioneered Horror & Speculative Fiction by Lisa Kroger and Melanie R. Anderson

Kim Stanley Robinson by Robert Markley.

Dramatic Long Form

Avengers: Endgame

Star Wars: Rise of Skywalker

Captain Marvel

Us

For All Mankind, Season 1

The Expanse, Season 4

The Mandalorian, Season 1

Watchmen, Season 1

Nominations will close on March 13th (at 2:59AM Eastern).

Further Reading

Asimov’s Behavior. Last week was “Science Fiction Day” a pseudo-holiday that coincides with Isaac Asimov’s birth a century ago. He was a prolific, essential writer within the field of science fiction, but was also a serial predator within the community. Alec Nevala-Lee, who wrote a wonderful book about the history of Astounding Magazine, wrote a damning piece for Public Books that looks at Asimov’s legacy in light of that harassment. I’ve been thinking a lot about Asimov lately, and how while he wrote much of the core of the genre, that legacy is growing more tarnished as people recognize that his behavior would have gotten him thrown out of the field if he were around today.

Legacies. Last week, author Mike Resnick died after a lengthy illness. I posted up an obit for him at Tor.com — a brief overview of his life and technical accomplishments within the genre. He’s been lauded over the years — earning a ton of nominations for his work. He was also someone who was approachable and friendly to the genre’s history when I interviewed him over the years about C.L. Moore, and some other things. He also bought my first (and thus far, only pro short story) for Galaxy’s Edge Magazine.

That said, legacy is a tricky thing. I’ll point to my good friend and co-editor Jaym Gates’ post about her experiences with him: Resnick and several of his ilk stood in the way of progress within SFWA, particularly when it came to the organization’s culture. I absolutely believe and agree with her assessments of authors like Resnick and Jerry Pournelle — they came at the genre from a certain angle, and while they provided me with insights over the years into the history of the genre, it was their angle that they shared. What’s unfortunate here is that their legacies could have been so much more.

Weird Futures. The Guardian has a great piece / profile / interview with William Gibson, who’s got a new book coming out soon, Agency. He talks about how Trump’s election threw the world in that book into doubt, forcing him to do some extensive rewrites. (I spoke with him a couple of years ago about this):

And, indeed, Gibson stopped setting his novels mainly in the far future around the turn of the millennium. He changed mode. “Since Pattern Recognition I’ve been writing novels of the recent past. They’ve tended to be published in the year after they actually take place. After the publication of All Tomorrow’s Parties [1999] I had a feeling that my game was sagging a bit. Not that there’s anything particularly wrong with that book – but I felt that I was losing a sense of how weird the real world around me was. Because I was busy writing novels and whatever, and I’d sort of glance out of the window at the day’s reality and I’d go: ‘Whoah! That was really strange.’ Then I’d look back down at my page and realise that that was stranger than my page, and I began to feel … uneasy.”

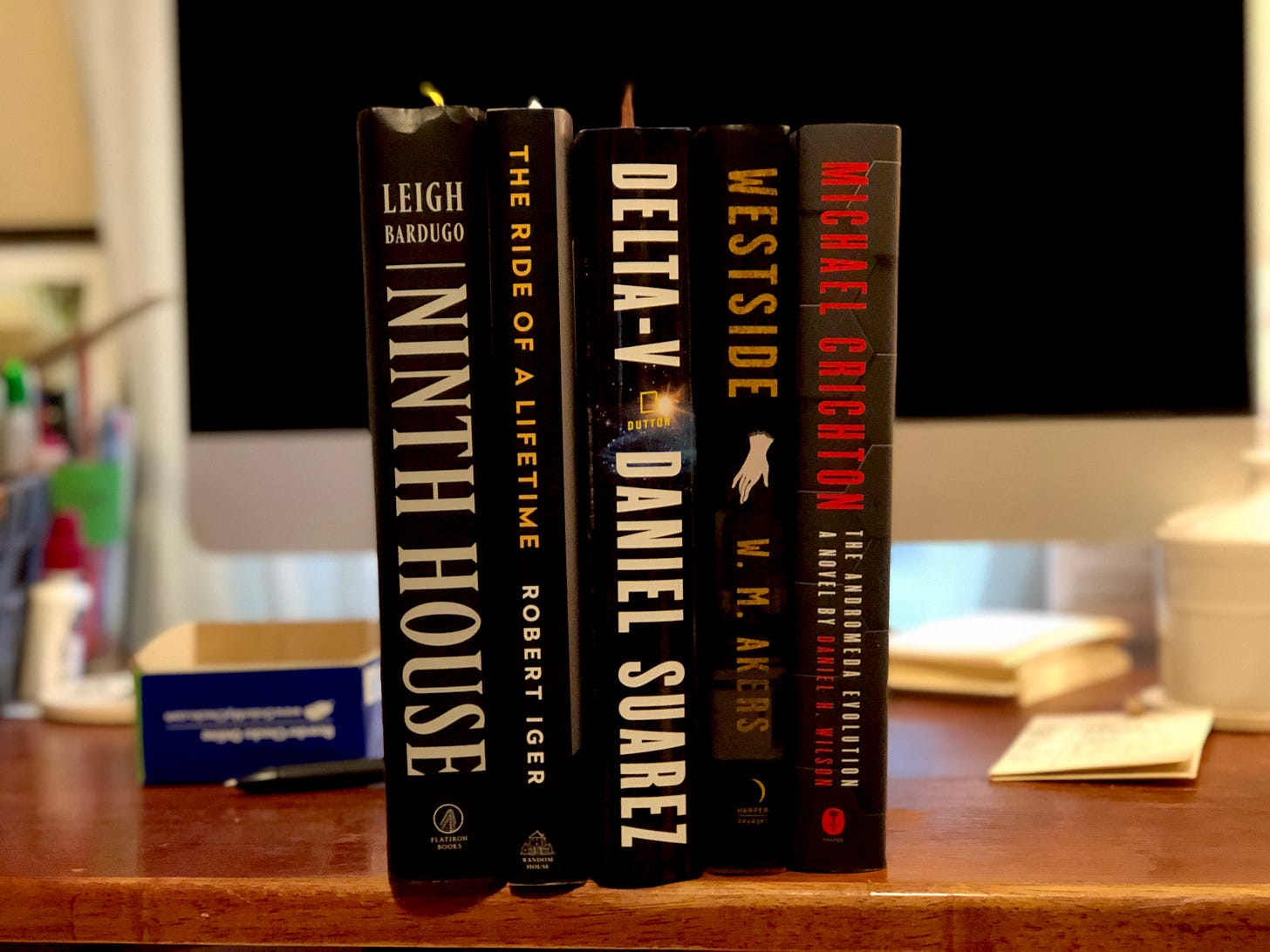

Currently Reading

I’ve since finished Gideon the Ninth, but I’ve got a good stack of dark books that I’m digging through: Andromeda Evolution (Daniel H. Wilson), Westwide (W.M. Akers), The Ride of a Lifetime (Bob Iger), Ninth House (Leigh Bardugo), and a couple of others. I’m in the alternate-chapters-in-different-books-stage while I figure out what I’m in the mood for.

That hasn’t deterred me from picking up others. I’m flipping through Karen Traviss’s Republic Commando: Hard Contact for a piece, and I recently picked up Moon of the Crusted Snow by Waubgeshig Rice, an Indigenous Canadian post apocalyptic novel, which sounds pretty cool, and I’m enjoying thus far.

That’s all that I’ve got for now. As always, thanks for reading. Let me know what you think, and what you’ve got on your to-read list.

Andrew