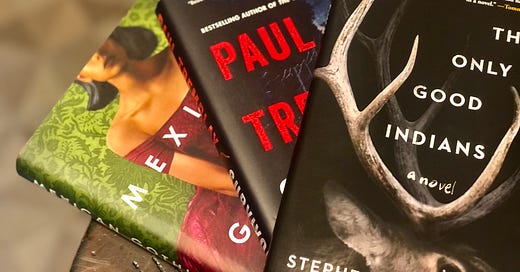

Three horror novels to keep you up at night in 2020

Silvia Moreno-Garcia's Mexican Gothic, Stephen Graham Jones' The Only Good Indians, and Paul Tremblay's Survivor Song

Hello!

As you’ve seen, it’s been a super busy week for this newsletter: thank you for putting up with the flood in your inbox this week as I close out a bunch of projects that have come up against some hard, topical deadlines like Halloween and the upcoming presidential election.

Also, happy Mandalorian day! I’m very excited that the show is back, but I’ll hold off on any concrete thoughts until a little further into the season, so as not to spoil folks. I’m waiting to watch the first episode tonight. To celebrate, however, I’ve finally finished* up my son’s Halloween costume. This is the way! It needs a couple of tweaks and some weathering, but I’m happy with it. I’ll likely do up a “how I made this” at some point.

* no costume is ever really finished.

Let’s dig in: I’ve got a trio reviews of three recent horror novels that are topical and pressingly relevant in 2020.

2020 has been the year for horror, from a global pandemic to persistent killings of Black civilians, to the rise of some truly scary rhetoric from extremist groups on the right. Over the course of this summer, I picked up a trio of horror novels, Silvia Moreno-Garcia’s Mexican Gothic, Stephen Graham Jones’ The Only Good Indians, and Paul Tremblay’s Survivor Song, and came away from each scared out of my wits.

Each of the books are powerful, thoughtful reads that provide plenty of things that kept me up late at night. But they’re each in their own way drilling down beyond scares, gore, and ghosts to provide the reader with the suspense and thrills they’re seeking: they each address deep-seated issues that are nestled at the core of the horrors in the books — and in everyday life.

Mexican Gothic by Silvia Moreno-Garcia

I loved Silvia Moreno-Garcia’s debut novel Signal To Noise when I read it back in 2015: it’s a rich, modern fantasy that blended its rich characters together music, magic, consequences, and family. I’ve been anticipating her latest, Mexican Gothic, initially because of the really phenomenal cover, but also because it’s a straight-up gothic horror about a decaying family and one young woman’s efforts to free her cousin from their grasp.

Set in the 1950s in Mexico, a young socialite named Noemí Taboada gets a letter from her cousin Catalina, who had recently married into a prominent English family, the Doyles, who presided over the silver mines of El Triunfo. The letter is disturbing: Catalina says that her new husband, Virgil, is trying to poison her, that the house is “sick with rot, stinks of decay, brims with every single evil and cruel sentiment,” but most worrisome: the house whispers to her and refuses to let her go.

Noemí’s father thinks that Catalina’s had a mental breakdown, and wanting to avoid a public scandal, dispatches her to the Doyle’s home, High Place, to figure out the situation and bring her home if necessary.

What Noemí finds when she arrives is a cold, gothic house. The Doyles are emotionally distant and strict, and High Place is a structure in decline.

But Catalina says that she wants to stay with her new husband, and Noemí works to figure out the family and what their story is. She’s disturbed by their casual racism and the family’s ancient patriarch, Howard Doyle, and soon begins to experience hallucinations and strange dreams herself.

Moreno-Garcia’s novel is a carefully tuned gothic tale, with elements of Dracula, The Yellow Wallpaper, Rebecca, and Jayne Eyre peaking out from behind the corners. It includes all of the necessary ingredients: a family in decline, a decrepit, gothic mansion, supernatural phenomena, and characters that have to contend with their reality unraveling around them, coupled with a slow burning sense of dread that drives the novel forward.

I also have to call out the house itself: it’s a glorious representation of the family’s decline, and Moreno-Garcia really nails its presence.

“Then, all of a sudden, they were there, emerging into a clearing, and the house seemed to leap out of the mist to greet them with eager arms. It was so odd! It looked absolutely Victorian in construction, with its broken shingles, elaborate ornamentation, and dirty bay windows…

The house loomed over them like a great, quiet gargoyle. It might have been foreboding, evoking images of ghosts and haunted places, if it had not seemed so tired, slats missing from a couple of shutters, the ebony porch groaning as they made their way up the steps to the door, which came complete with a silver knocker shaped like a fist dangling from a circle.

And like all good gothic horror, it’s a book that holds a stark social commentary at its core, examining the colonial attitudes of High Place. The Doyles, Noemí discovers, came to Mexico strip the country of its wealth, much like the Europeans who came before them. But at some point, there was an illness that spread like wildfire throughout the mining town, and the family has fallen further and further with each year. I don’t want to spoil the reveal, but Noemí and Catalina’s arrival are integral to the family’s plans — a desperate hope to resurrect their bloodline and family fortunes, using deeply racist logic to justify their actions.

It’s a deeply gripping story that cuts to the root causes of the racial divide in the Americas, the result of the encounter between two alien cultures, one that sociopathically exploits and dehumanizes the other. Noemí is an exceptionally vivid, powerful character that Moreno-Garcia transplants into dull, decaying surroundings, showing that the real horror is everything she loses through assimilation.

The Only Good Indians by Stephen Graham Jones

Stephen Graham Jones’ The Only Good Indians opens with a horrific scene. A young Blackfeet man, Ricky, had left home and joined a mining crew in North Dakota, and makes his way through a bar — one of two in the joint — and encounters a terrifying, spectral presence in the parking lot. It’s an elk, and as it sets off car alarms in the parking lot, the angry, drunk miners in the bar target Ricky and brutally murder him.

The murder sets the tone for what’s to come as Jones jumps from character to character — Lewis, Ricky, Gabe, and Cassidy — four childhood friends who grew up on a reservation, and who are each visited by this spectral presence. A decade before, they embarked on a hunting expedition in a forbidden part of the reservation, one reserved only for their tribe’s elders, trying to make the best of a slow hunting season. It’s there that they hit the jackpot: a herd of elk that have huddled together in the middle of a snow storm, easy targets for the four young men. Shen the shooting stops, eight of the creatures are dead, but one refuses to die — it keeps trying to escape, despite its mortal wounds, and it isn’t until they finish her off that they realize that she was pregnant.

The four are caught by tribal authorities and forced to leave their kills behind, and a decade later, the past begins to catch up with them. Lewis has moved on, working as a mailman, and living with his girlfriend, Petra in a house they share. He too is soon haunted by the specter of that elk that refused to die, injecting him with paranoia, and he hatches a plan to try and kill it before it kills him, a plan that backfires spectacularly. The elk soon turns its attention on Gabe and Cassidy, stalking and torturing each of them in turn before striking.

There’s plenty of gruesome scenes here: Lewis slowly loses the people around him in some cringeworthy ways — from his girlfriend’s nasty fall onto the edge of a brick fireplace to a murder of a coworker he believes is really the ghost of an elk — but where Jones really shows off his mastery is the slow burning tension that permeates the pages. As Lewis descends into paranoid insanity, we can see what he can’t: that he’s being manipulated by the creature into committing some horrible acts. Even once the characters begin to realize what’s happening, it’s hard to break away from the game before it’s too late.

The novel is more than just a revenge fantasy from a wildlife creature — Jones points to a flaw at the heart of each of the characters: a sort of corrupted masculinity that drove their initial slaughter, and which drives their actions as they try desperately to survive. Ricky joined a mining crew, enduring the racism and intense, dangerous labor to be a man. Lewis is tempted by a coworker, while Cass and Gabe contend with alcoholism and poverty that has ruined their relationships with family or brought them into conflict with the law. The spectral elk doesn’t really need to do much in order to extract her revenge from each of the four men: she just has to push them in the right direction, and leave them to marvel at the horrors that they have perpetuated. It makes for a tense, frightening, and gripping read.

Survivor Song by Paul Tremblay

Reading Paul Tremblay’s latest in the middle of a global pandemic was an interesting experience. I had to put this down more than once, because at times, it just felt too real. An aggressive form of rabies has begun to spread, infecting its victims within a matter of hours, pushing them to violently attack and bite those around them, spreading the illness even faster through the community.

As the book opens, we meet Natalie and Paul, who are attacked in their home by a neighbor. Paul is killed and Natalie is bitten. She calls her friend, Rams — Dr. Ramola Sherman — a doctor at a local hospital that’s been dealing with the influx of patients. There’s a complication: Natalie is pregnant and nearly due, and it’s a race against time and across the city to get a vaccine and bring her to safety before she gives birth.

I’ve admired Trembley’s recent novels (A Head Full of Ghosts, Disappearance at Devil’s Rock, and Cabin at the End of the World) for his take on the horrific: he has a light touch, letting the reader wonder if what the characters are experiencing is really supernatural, or just in their heads. With each book, he’s placed his own spin on established genre tropes — exorcisms, ghosts, or home invasions — and with Survivor Song, he turns his attention to zombies.

There’s been a glut of zombie stories out there in the last decade, from straight-up horror like The Walking Dead and ZNation, to the more inventive, like Santa Clarita Diet or iZombie. It’s a trope that’s been done to death (sorry), but Tremblay’s managed to put a new perspective on it, examining the crisis as a public health issue. The violent residents of Massachusetts that Rams and Natalie have to contend with aren’t the goulish undead, but are people who are desperately, fatally ill. Tremblay sprinkles in plenty of pop culture references, from The Cranberries’ ‘Zombie’ to references to the various films and shows out there, pushing back on them with a sense of realism.

The horror in Survivor Song comes with its relentless pace: the book takes place over the span of a couple of hours as Natalie begins to deteriorate, leaving messages for her as-of-yet-unborn daughter as she and Rams try and get help from one hospital after another.

The other facet of the horror comes from the obvious, mirroring the last six months that we’ve endured this pandemic. Toward the end of the novel, one particular passage jumped out at me:

“In the coming days, conditions will continue to deteriorate. Emergency services and other public safety nets will be stretched to their breaking points, exacerbated by the wily antagonists of fear, panic, misinformation; a myopic, sluggish federal bureaucracy further hamstrung by a president unwilling and woefully unequipped to make the rational, science-based decisions necessary; and exacerbated, of course, by plain old individual everyday evil.

While the book arrived in bookstores in the midst of the pandemic, Tremblay tells me that he wrote the book long before it took place. But while it makes for a hard read because of how closely elements of it have tracked with real life — lockdowns, the panic buying in stores, the sense of dread and uncertainty — the book shows that the ingredients needed for such an event were systematically laid by evil and corrupt men who peddle in misinformation, anti-science rhetoric and who are unable to confront the challenges before them. That’s the real horror, and it’s one that doesn’t require a reader to suspend their disbelief.

Fandom isn’t immune to online radicalization & other paid posts

Between Halloween and the Election coming up, it felt like there was a bit of a crunch for some deeper pieces about horror and gloom: subscribers got a couple of posts this week:

This piece has been percolating for a while, and it’s one that’s hit home for me. I recently had a conversation with a friend that made it clear he’s been circling the drain with conspiracy theories within the Star Wars world. It’s worrisome, because it’s not a far jump to more mainstream and harmful conspiracies.

This essay came about after I spoke with VPR about the namesake of a local road, which got me thinking about how monsters come from the boundaries between where we humans live and the wild outdoors.

I had a longer preview of this piece here, but there’s been a bunch of signups since that went up, so I figure I’ll point y’all to it again. This piece takes a deeper look into the history of Dragonlance and how it changed fiction, as well as some thoughts on the recent lawsuit by its creators against Wizards of the Coast.

These are all posts that took a bit of time and effort to assemble. All three posts took anywhere from a couple of days to a couple of weeks to put write and edit, and required some deeper background research on their respective topics, as well as a number of interviews each. This work is directly helped by your support — I’ve been able to set aside time to write these, sign up for transcriptions, and so forth. If you want to help (and read the full pieces), please consider signing up for a full subscription.

Currently Reading

Here’s the usual long list of things that I’m working my way through. This list hasn’t changed too much from last week.

Meteorite: How Stones from Outer Space Made Our World by Tim Gregory, about meteorites and the impact (heh) they’ve had on our civilization.

The Human Cosmos: Civilization and the Stars by Jo Marchant. Nice companion Meteorite, about how astronomy has impacted and directed civilization and knowledge.

Pantheon by K.R. Paul. I’m not too far into this one, but it’s a neat military fantasy, about an Air Force officer who discovers that she has the power to teleport, and is inducted into a special unit.

Embers of War by Gareth Powell. Fun space opera. I’ve been listening to the audiobook and reading it, and I’m really digging the world. I’ve picked up the other two installments of the trilogy recently.

Black Sun by Rebecca Roanhorse. Epic fantasy set in central America. I’m really enjoying this one.

You Look like a Thing and I Love You by Janelle Shane. This is a book I’ve had on my to-read list for a while, and it’s about machine intelligence. It’s very fun, and nicely accessible.

Also on the to-read list? Alix E. Harrow’s The Once and Future Witches, Peter Watts’ Blindsight, Kim Stanley Robinson’s The Ministry for the Future, and Micaiah Johnson’s The Space Between Worlds. Soon.

Further Reading

Costume appropriation. Kendra Beltran has an excellent piece up on Cosplay Central about cultural appropriation and costumes.

Crowdfunding woes. This is some unfortunate news: Master Replicas has converted its Chapter 11 bankruptcy to a Chapter 7, meaning that it’s liquidating its assets. The company had relaunched a couple of years ago with a HAL smart speaker, but it never delivered product to its backers on Indiegogo. It’s a shame, because I saw one of the products at NYCC back in 2018, and the result was pretty cool. But it’s pretty shitty that they didn’t follow through.

Goodreads 2020 Choice Awards. Goodreads has launched this year’s iteration of its choice awards, and there are some really fantastic titles on the ballot. It’s currently in its first phase, and after that, it’ll move onto a semifinal round and final round.

Mandalorian Cosplayers. Because The Mandalorian is back this week, I figure it’s a good time to point people to my feature about how fans have pushed The Mandalorian culture forward. It came out earlier this year on Polygon, and it’s one of my favorite things that I’ve written this year.

The Midnight Sky. Netflix released a trailer for its upcoming George Clooney-helmed film The Midnight Sky. It’s giving me a Gravity / Interstellar vibe, which I’m digging. It hits on December 23rd.

New Chinese SF Anthology. Tordotcom announced a new anthology of short stories, specifically with a focus on women and nonbinary creators from China, The Way Spring Arrives, edited by Yu Chen and Regina Kanyu Wang. It looks like a pretty cool book, but it’ll be a while before it hits stores: 2022.

October Book List. John at Black Gate highlights my October book list, which he calls “exhilarating and frustrating…It’s like being rushed through a tantalizing buffet — it looks fantastic, but no way you’ll have time to try it all.” I think that’s accurate.

Vermont’s Ghostmaster General. Seven Days has a great profile of Joe Citro, an all-around good guy and Vermont’s expert on all things supernatural.

That’s all for this week. If you haven’t already, please go vote (do it in person!), and enjoy Halloween, however you’re celebrating. Stay tuned: on Monday, I’ll have the usual monthly book list.

Andrew

I very much enjoyed Survivor Song. And, as you pointed out Tremblay had written this long before the Covid pandemic. His description of our circumstances seem prophetic... especially in a scene in which the protagonists encounter armed men that might as well have been wearing certain red baseball caps.

If anyone is a fan of The Only Good Indians, they might be interested in viewing an indie zombie movie called "Blood Quantum". It was on Shudder streaming service, but it might be possible to see it elsewhere. The same tone of Only Good Indians is invoked in the movie told from the POV of indigenous people on a reservation.