Hello!

This week became unexpectedly busy, right as the temperatures began to drop here in Vermont. Where it was 60s and 70s a couple of weeks ago, it’s now in the 40s and 50s. I like this time of the season, even as my body takes a little while to adjust to the cold while I tap away in my workspace.

When I announced a firmer mission for Transfer Orbit a week or so ago, I put together a formal editorial calendar for it, plotting out the upcoming roundup newsletters (like this one), some reviews, essays, and podcast episodes, I gave myself a bit of a heart attack when I realized how quickly I had to move on the first couple of podcast episodes for New Worlds. With Dune now delayed, there’s a bit of breathing room, and my sense of panic has evaporated — for now. There’s a lot coming up, and I greatly appreciate that you’re here to follow along.

Interview with Larry Niven

One of my favorite books of all time is Larry Niven’s Ringworld: for me, it epitomizes the entirety of 1960s/1970s science fiction: interstellar megastructures, galactic civilizations, and a bit of a quest-style adventure. It does have its issues, reading it fifty years later, but when I dipped into it briefly recently, I was struck at how quickly it moved, and how much fun it was.

The novel first hit bookstores in October 1970: a full half-century ago, and with that milestone in mind, I spoke with Niven about the novel earlier this year, and chatted with him about the book and what it’s like after half a century.

This interview has been edited for length and clarity.

I wanted to go back to the beginning, and was wondering if you’d tell me about the world you grew up in. I know you were born in the late 1930s, and grew up during the post-war era. How did that environment of economic and technological growth shape your worldview when it came to science and technology?

I was only seven when the war ended, so I didn't have any strong economic knowledge. In fact, I didn't pick up any economic knowledge until I started collaborating with Jerry Pournelle. But I was in love with with jet planes. I figured our future was all rocket ships. I think in Flash Gordon, they felt the same.

How did the space race influence you?

Yes, certainly. I don't know what to tell you that you haven't heard from everyone else. I was in in the middle of the street driving to a party at Bjo Trimble’s house, the famous science fiction fan. She was throwing a party for the landing on the moon. And I was in a car still on the way when they decided to leave orbit. I remember the thought, “wait a minute — have we thought this through completely?”

What was that party like?

The party was fun. There was a lot of sitting around dozing, because the astronaut were sitting around dozing. They’d just going through an ordeal! They needed to rest.

What were some of the stories that attracted you, aside from the future being full of rocket ships?

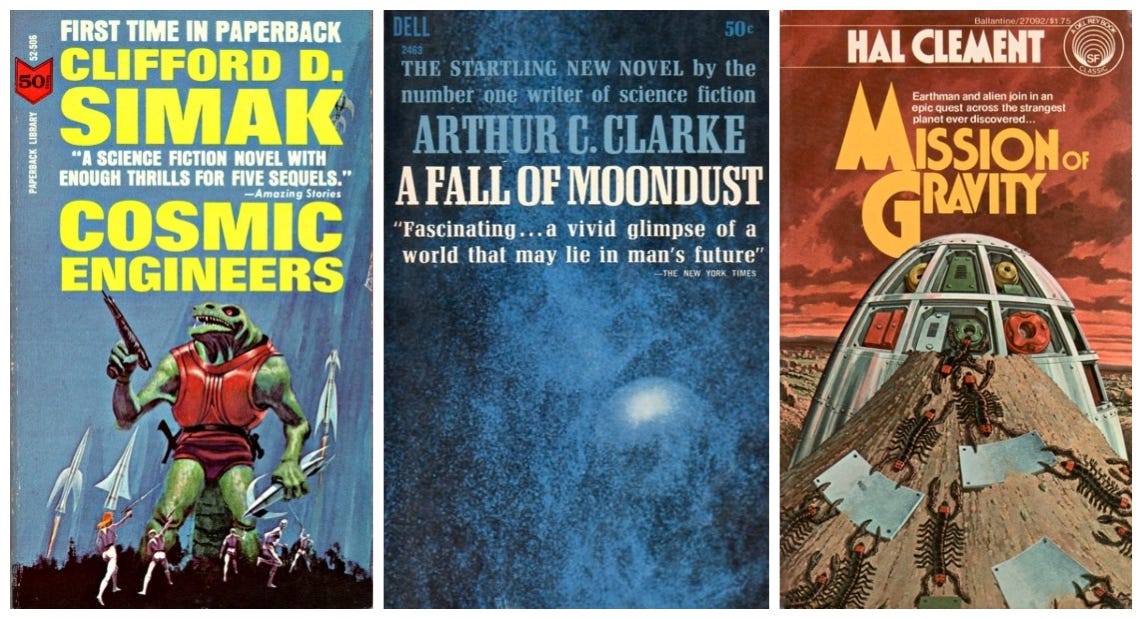

There was a novel called the Cosmic Engineers [by Clifford D. Simak]. And it wasn't terrific but it set the stage for large ambitious stories. Arthur Clarke was also one of the best writers around, and he got my attention. And then I got to Hal Clement's Mission of Gravity, which is canonical.

It was the notion that they were describing a reality. I did start with fairy tales, [but] I didn't get that much knowledge from them. I graduated to science fiction with Robert Heinlein, and Jack Anderson, and Poul Anderson and Jack Vance. Vance is one of the best writers around.

I had all the magazines, including the failures. A lot of the magazines have collapsed, and were collapsing even in the 1960s and 1970s.

Yeah, as bookstores and chainstores came about, right?

Yeah. We used to get our our magazines and paperback books in drugstores. I heard many tales — Robert Gleason, my editor on several books, he said that they condensed all their distributors down to six, and then they fired all the old guys to condense their manpower. And then they realized that all the people they fired were the only ones who knew where the markets were. It seems like the publishing industry is always in trouble. It’s certainly in trouble now.

Going back to some of the original influences on Ringworld, you basically had the idea to take a sliver out of a Dyson sphere, right?

It's obvious once you think about it right now. A Dyson Sphere works if you've got cultured gravity to bring gravity around the inner surface, but generated gravity is supposed to be impossible. It's one side of relativity — no anti gravity. Well, with no anti-gravity, you're depending on spin gravity. And if you spin the Dyson sphere, you can get gravity along the along the equator. But nowhere else, so I just worked with the equator. The Ringworld is a Dyson sphere.

When did you first come across Freeman Dyson? What was what was your introduction to him?

I've only met him once. It was at a party that the Pornelles used to throw at AAAS meetings. We got him in as one of our guests. I didn’t talk to him much — I wish I had — but he didn’t talk much, but when he spoke, everybody listened.

You were at the Milford Writer’s Workshop when you first came up with this idea?

Yeah right. I was at the Milford Conference at Madeira Beach [Florida], the only time the Damon Knight and Kate Wilhelm tried that.

Betty Ballantine showed up, and I was in the middle of writing Ringworld and I had just realized what would happen if you punched a hole through the Ringworld and started letting air out. You get a cloud formation that looked like a human eye, eyebrow and all. I remember explaining this to Betty, whether she was listening or not, I don’t know. She was polite about it.

Ringworld kind of told itself. I was winging it, and occasionally an idea would pop up and I know something more about the place. And a friend named David Gerrold suggested that I do something with the Fist of God mountain, and that’s where I realized where my ending was.

So this was one of those “build it as you go” books, rather than something you plotted out?

Yes. I think a lot of odysseys — this book is an odyssey — and I think a lot of odysseys are written that way, including the original one. You don’t have to solve every problem — you can leave some of them behind you!

What was the reaction to Ringworld when it was first published?

It was as good as I could have expected. I was a little worried and afraid people would consider it ridiculous — it was about a ridiculously large, engineering device.

Why do you think it resonated with fans?

It’s big and plausible. You can put it into your head and derive implications. Like, how strong does the surface have to be so that it doesn’t get torn apart? Someone in Oxford came — it has to be about the same strength of the tensile strength of a nuculus.

Lester Del Rey pointed out that there’s enough room on the Ringworld for many, many stories — more than Edgar Rice Burroughs ever wrote set on Mars. Lester wanted me to write a lot of stories set on the Ringworld.

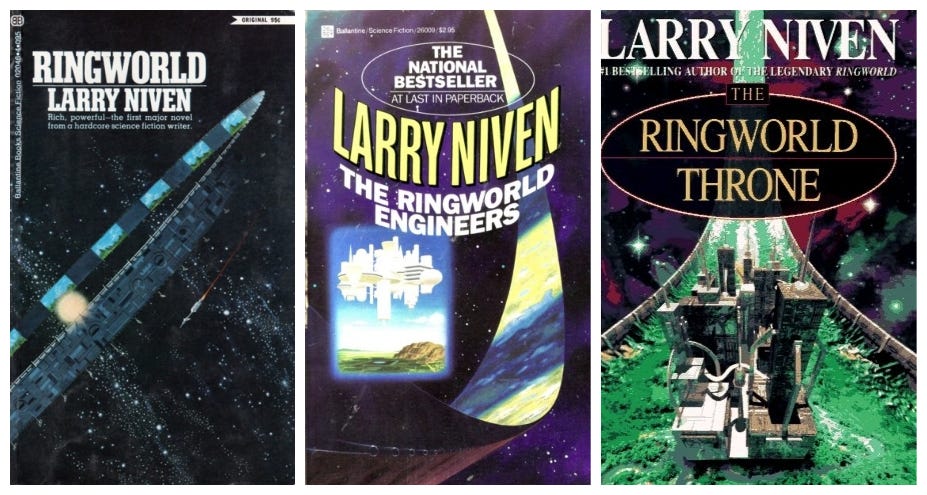

I didn’t. I only did four.

Why didn’t you? What made you restrain yourself?

I never write a sequel until I have more to say. And for Ringworld, it took another 25 years — 10 for Ringworld Engineers and another 15 for The Ringworld Throne.

What does it look like looking back after fifty years?

You know? It’s annoying! I’ve waited this long, and there’s still no movie. I sold the movie rights more than 40 years ago, to a guy who was going to make a cartoon out of it. He still has the rights, because I signed the wrong contract.

What would you hope that an adaptation would have?

I’d like to see them doing it about in the way they did it in the book. No, take that back. I didn’t go full on off in the first book. I’d like to see them borrow material for the second book, and they could borrow concepts from the other three.

Looking back at the last 50 years, how have you seen science fiction change?

They’ve gotten more ambitious. They’ve gotten harder science, mostly. There are a lot of books out there where faster than light travel is impossible, for instance. And certain things that were considered impossible are no longer. There are a lot of good writers out there.

Belated October Addition

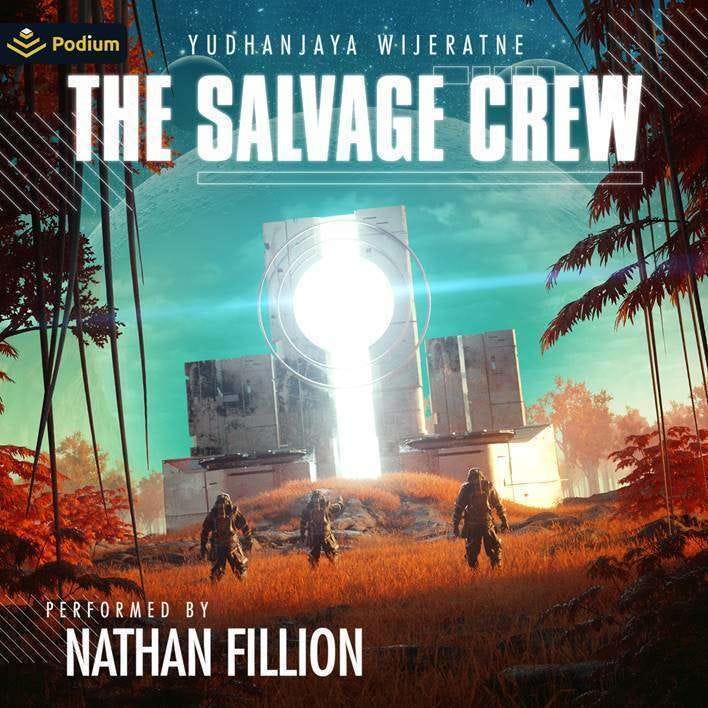

I’ve got a belated addition to the October book list, by way of Syfy Wire: Yudhanjaya Wijeratne’s The Salvage Crew.

Wijeratne is a rising star from Sri Lanka, and he earned a Nebula nomination for the novelette Messenger (cowritten by R.R. Virdi) in 2018. He’s also a data researcher and what’s really interesting about this novel is that he used AI to help write it. He used OpenAI and some original code to help create the environments and characters as he wrote.

The book itself sounds pretty exciting, too: An AI overseer and a crew are dispatched to an aging spaceship for a salvage job at the far end of the galaxy. The job proves to be more challenging than they thought: the world is inhabited by massive animals, while another crew is trying to swoop in to take their target out from under them. What’s also exciting is that Nathan Fillion (of Firefly and The Rookie fame) is narrating the audiobook. I’ve since preordered it — it sounds very much like my thing, and I’m excited to see what it brings.

The book is due out on October 27th on Kindle and audio.

Current Reading

I’ve got a handful of books that I’m working through that have carried over from last week: Survivor’s Song by Paul Tremblay and Black Sun by Rebecca Roanhorse. But I’ve also picked up K.R. Paul’s Pantheon, which looks like a bit of fun, and I picked up an advance copy of Ring Shout by P. Djèlí Clark, which I’m enjoying. I’m also listening to Gareth Powell’s Embers of War, which I’m finding really engrossing, and I’m a little annoyed at myself that I missed out on a couple of years ago when it was first coming out. Ah, well.

I’m headed out for a couple of days to my family’s place in New York, which usually means that I can plow through a book or two.

Further Reading

*Another* Ken Liu series. Ken Liu’s going to be everywhere on your TV screen before too much longer. The Cleaners will be his fourth series in development, and the story drops on Amazon in December.

CJA Newsletter. Charlie Jane Anders has joined the legions of authors setting up newsletters. You can read the first excellent issue here.

John Joseph Adams Books discontinued. John Joseph Adams — who I used to work for at Lightspeed Magazine — announced that Houghton Mifflin Harcourt had discontinued his dedicated science fiction imprint. I’m bummed, although not totally surprised to see it: he published some well-known authors, but none of them really seemed to take off.

New Simon Stålenhag! A new art book from Simon Stålenhag is always a cause for celebration. The Labyrinth is on Kickstarter now, and I couldn’t back it fast enough.

N.K. Jemisin, certified genius. The John D. and Catherine T. MacArthur Foundation has awarded N.K. Jemisin a MacArthur “Genius” Fellowship! This is really fantastic news, and it’s incredibly well-deserved.

Space Junk. Raffi Khatchadourian at The New Yorker has a great long read about the growing problem of space debris in Low Earth Orbit.

That’s all for this week. Coming up: I’ve got an in-depth interview with Chris Brown, author of Failed State. Subscribers will get the audio version, which I’m working to clean up now. I’ve also got a review coming up of a trio of horror novels — stay tuned. After that, an essay about horror at the edges of nature and a feature about AI wargaming, both for subscribers.

In the meantime, let me know what you’ve been reading lately!

Andrew